Kentucky Battery Plant Joins United Auto Workers in Close Vote

BlueOval SK workers at a huge new battery plant in Kentucky have voted to join the United Auto Workers. They faced bitter opposition by plant managers as well as some firings. However, some ballots are being challenged. Photo: UAW

Kentucky battery plant workers at the BlueOval SK Battery Park (BOSK) in Glendale have voted to join the United Auto Workers. The workers make batteries to power Ford’s all-electric F-150 Lightning pickup truck and E-Transit cargo van.

On August 27 at 10 p.m., an unofficial tally showed 526 yes and 515 no votes, with 41 challenged ballots. There were 1,200 eligible voters; turnout was over 90 percent. The UAW called the vote “a major step forward for workers who stood up against intense company opposition and chose to join the UAW.”

“We’re feeling pretty confident, I think we’re gonna win,” said battery worker Halee Hadfield via text message on August 23. “Things are really ramping up across the whole plant and people are pissing off the plant managers by simply wearing shirts, hats, and buttons with the UAW logo on them.”

DISPUTED VOTES

The outcome of the election will ultimately hinge on the 41 challenged ballots. The union called those ballots “illegitimate,” and called on Ford to “drop their anti-democratic effort to undermine the outcome of the election.”

Maintenance and production workers were eligible to vote. But the status of Safety Emergency Response Team (SERT) employees was left in limbo: election rules agreed to by the company and the UAW permitted them to vote, but said their eligibility would be decided after the election. Their ballots are being challenged by the union.

“The challenged ballots are not part of the group of workers who built their union from the bottom up,” the UAW said in a statement. “They deserve to have their own union, in an appropriate bargaining unit with a representative of their own choosing.”

SOUTHERN ORGANIZING PUSH

“I’m just under 30 years old, and I’ve been trying to organize my entire adult life,” said Derek Doherty, a production operator, who has tried to organize with the Service Employees and the Teamsters at previous jobs. “It’s just been beautiful,” he said about the union drive. “Everybody knows what we’re here for and why we’re doing it.”

Hadfield had predicted a win by 57 percent. “Unfortunately, a lot of people bought the company’s bullshit,” she said the night of the vote count.

Shortly after the successful 2023 Stand-Up strike against the Big 3 automakers, the UAW committed $40 million to new organizing with the intent of doubling the union’s membership by aggressively organizing 150,000 non-union workers, especially in southern auto manufacturing and newly built battery plants.

Ford’s joint venture battery plants in Kentucky and Tennessee were the next targets in this organizing push. And the UAW’s latest effort to breach one more citadel in the South comes with big potential obstacles, as Ford will appeal the contested ballots, and this may give the Trump administration an opportunity to influence the outcome through the National Labor Relations Board.

UNION EXPERIENCE

Hadfield and many of her co-workers were union members at previous jobs. For four years, Hadfield was a member of the Communications Workers’ industrial division, IUE-CWA, at the General Electric-Haier Appliance Park in Louisville, an hour’s drive from the BlueOval plant.

Others had the protection of UAW contracts at auto parts suppliers or Ford’s Kentucky Truck and Louisville Assembly Plants, or they have family who were Teamsters at UPS or grocery workers at Kroger.

The battery park is a joint venture between Ford and South Korea’s SK On, an affiliate of South Korea’s second-largest conglomerate.

In July, the UAW joined forces with the militant Korean Metal Workers’ Union in hopes of changing BOSK’s status as “the only union-free company among the joint ventures between Korean battery manufacturers and U.S. automakers,” according to The Korea Times.

SK On and Ford’s partnership involves creating twin electric battery manufacturing facilities in Kentucky, and in Stanton, Tennessee. The Stanton plant is slated to start production in 2025 after a pause last year. The Kentucky battery park became fully operational on August 19. The facility is expected to eventually employ over 5,000 workers.

“Whatever the powertrain is, we’re going to be there,” UAW President Shawn Fain said earlier in the month at a rally. “We’re not going to run from [technological] advances. We have to embrace it and figure out how we make it work for working-class people, not just for business or just for the rich.”

The union notched a big win in its new organizing push in auto in April 2024, when 4,300 workers at the Volkswagen plant in Chattanooga, Tennessee, voted to join the UAW. It was the first auto assembly plant election the union had won in the South since the 1940s.

WINS AND LOSSES

A month later, however, the union fell short of winning an election at a Mercedes-Benz plant in Alabama. It has not filed for any elections at other Southern assembly plants since, and the Volkswagen workers are still fighting for a first contract.

Earlier this month, in another blow, workers at a Navistar engine plant in Huntsville, Alabama, voted 142 to 73 against joining the UAW following an aggressive anti-union campaign by management, including a personal visit to the plant by the parent company’s CEO and the reinstatement—days before the vote—of a health insurance plan the company had taken away last year. According to the union, those moves violated the neutrality agreement in its contract at other UAW plants and reversed course on its card-check certification agreement to recognize and negotiate with the union once a majority of employees sign up.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

Battery plants have been a bright spot in the UAW’s organizing efforts. Workers at Ultium Cells, a joint venture in Ohio between GM and LG Energy Solution, joined the UAW through an election in December 2022, and won a first contract in June 2024. Ultium Cells workers at another plant in Tennessee joined the UAW through a card-check agreement last September, a victory clinched during the Stand-Up strike; GM agreed to recognize the union through a majority sign-up process as part of the agreement that ended the strike. At the Kokomo, Indiana, battery plant StarPlus Energy, a joint venture between Stellantis and the South Korean company Samsung SDI, the company agreed to recognize the UAW this May after a majority of the 420 workers signed cards to join the union.

Ford, however, has balked at agreeing to neutrality at its joint ventures or folding its battery plants into its master contract with the UAW. During the Stand-Up Strike, Ford CEO Jim Farley accused Fain of “holding the deal hostage over battery plants.”

BITTER COMPANY CAMPAIGN

Since then, Ford has taken the gloves off. It launched a bitter anti-union campaign at BOSK, holding the vote back for nearly five months after finally agreeing to an election date in June, and dispatching supervisors to harass union supporters wearing UAW shirts to chill the organizing drive. The UAW has filed four unfair labor practice charges, alleging that BOSK destroyed union materials, fired pro-union workers, and threatened to close the facility if workers voted to unionize.

One notable talking point, said Hadfield, is the company’s use of Trump’s rollback of electric vehicle credits to claim its financial viability is in jeopardy. The company falsely claimed to have lost a $9 billion loan from the Department of Energy that it had already obtained under the Biden administration, Hadfield said.

BOSK workers’ starting pay is $21 an hour, compared to $26.32 for UAW Ford workers, whose earnings increase to over $42 an hour after three years. But it’s not just about dollars and cents.

Doherty, a production operator, started in late June and signed a union card on his first day at the plant. During mandatory training at a nearby facility, management painted a rosy picture, he said, claiming that there was no division between salary and hourly workers, “it's just one big family.” But as soon as he arrived at the plant, he noticed the power managers wielded through favoritism and decided to join the organizing effort.

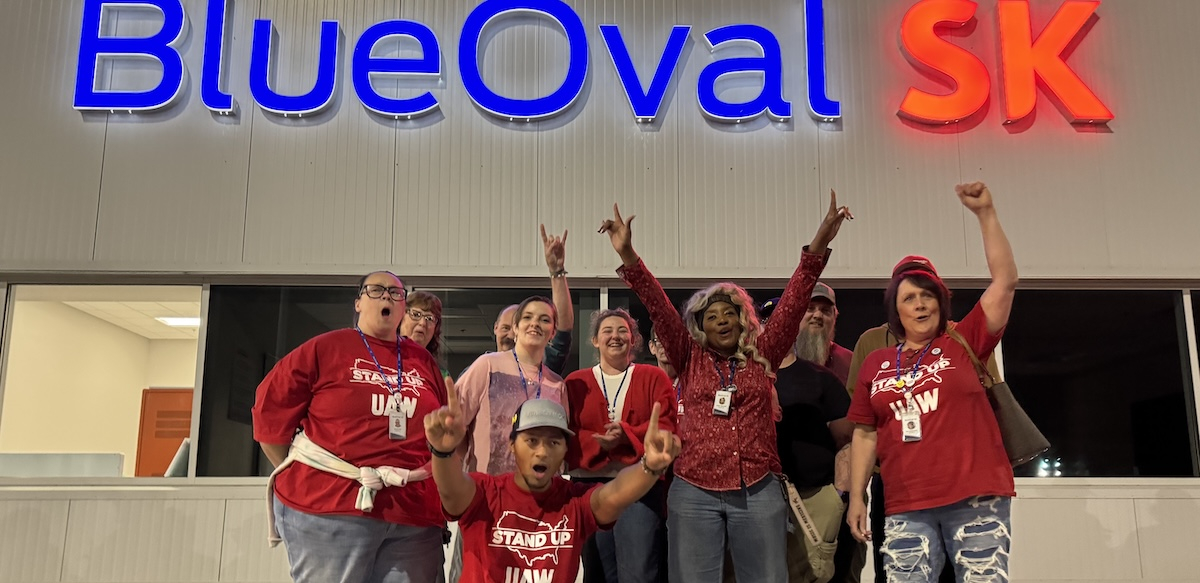

He described the company’s anti-union push as a typical assault on workers’ minds: lies and intimidation. “They’ll do the exact textbook definition of an unfair labor practice but then toss in one sentence that adds just enough of a caveat to make it slip by.” He described captive-audience meetings where workers were forced to sit through anti-union harangues from management.

Managers would shut down the line, he said, and then announce that there was a meeting going on, saying “it’s completely voluntary, but we really think you should go.” That’s not a real choice, said Doherty. “The line is shut down, everybody else is going. There’s not really much else to do in there.”

Hadfield said she and her co-workers are vocal about their union support but they are less visible with their union gear. “Because of the retaliatory firings and people getting threatened with all kinds of bullshit, there are a lot of people who used to wear a red shirt that don’t anymore because they’re scared.”

In the course of the nine-month organizing push, BOSK management has fired three union organizing committee members. But workers remained committed to the organizing drive, saying the company has been the best organizer.

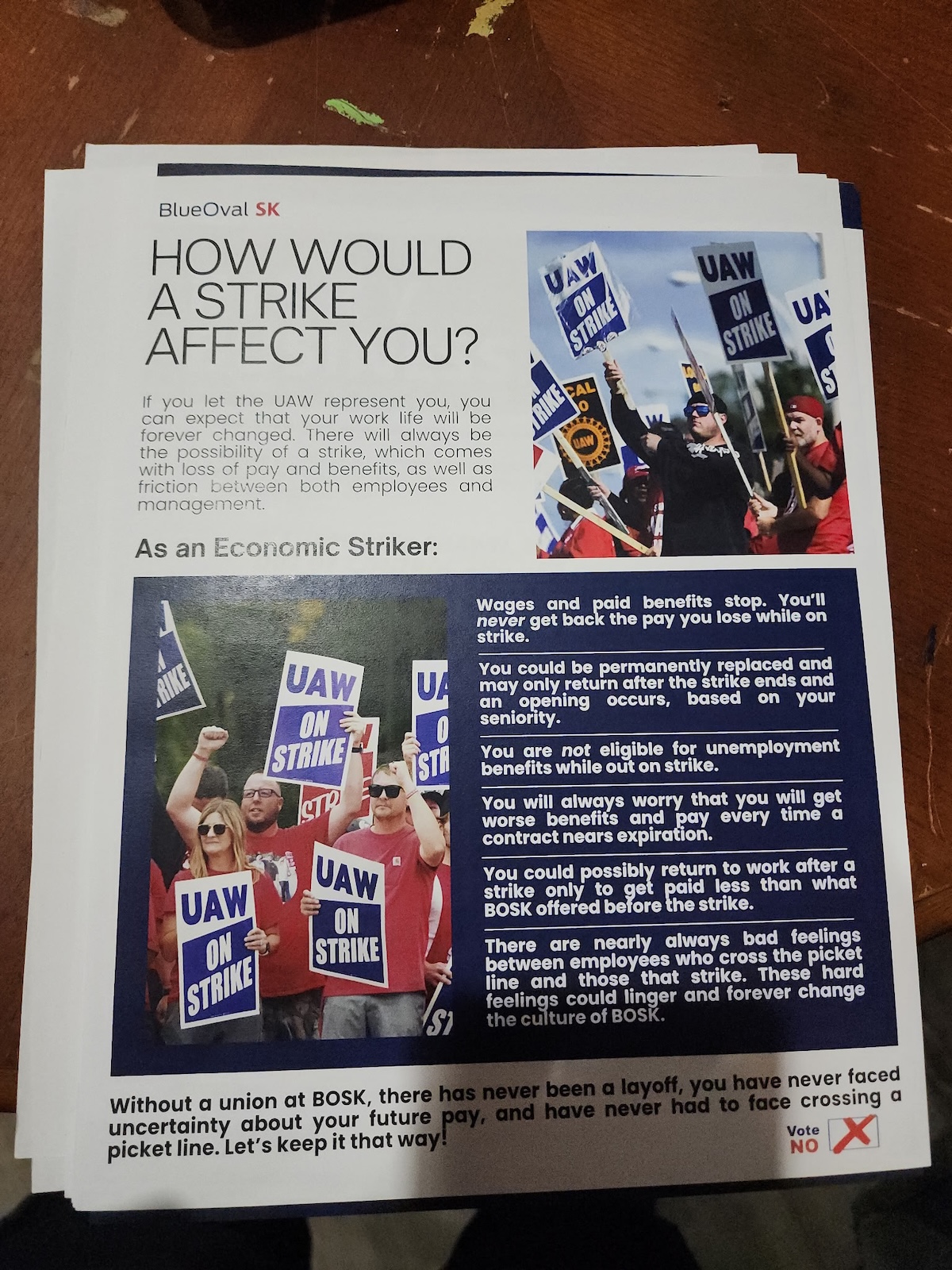

Company management also used recent internal divisions in the UAW to attempt to undermine support for the union. Flyers passed out by supervisors (see image at right) quoted opponents of the union’s aggressive organizing and bargaining strategies under Fain, and attempted to sow fear among workers about the potential ramifications of a strike (see image above). One flyer concluded by asking: “In this unstable environment—with a history of hostility, layoffs, and financial corruption—is this the type of organization you want to trust with your livelihoods?”

DANGEROUS SLURRY

Health and safety concerns loom large at the plant. A May Louisville Courier Journal investigation found that unsafe working conditions ranged from chemical exposures to blocked emergency exit doors to mold contamination to injury and respiratory illness. As Labor Notes reported last November, a big motivation to organize a union at BOSK, as it was at Ultium Cells, stemmed from safety concerns, especially exposure to hazardous powders from chemical leaks, electric shocks, explosions, and fires.

Rob Collette was previously a member of IUE-CWA at General Electric-Haier Appliance Park. He left after five years to work at BOSK because it was closer to home and he thought battery plants are the future. “The technology, the facility, the machinery,” he told Jacobin in March. “It’s blown my mind.”

Collette hired in while the plant was still under construction, but tripped on construction debris and fractured his hip. The experience fortified his support for the union drive to fix the company’s negligence. “Nobody feels safe,” he said.

“Roughly three weeks in, I just mentioned to a co-worker one day, ‘Golly, if we don’t get the UAW in here, I don't know if I can stay,’” said battery worker Bill Wilmoth back in November.

“We started running into a myriad of safety issues,” said Wilmoth. “We are taken into a plant that is in construction, and we’re being asked to navigate that, and never really given clear instructions on things like what happens if there’s an emergency? How do we evacuate? How do we deal with the raw material chemicals?”

“Just today, there was an accident where a bunch of people got sprayed with electrode slurry,” said a worker on August 26 who we’ve granted anonymity to protect from company retaliation. When handling the electrode slurry, workers can come into contact with a hazardous solvent known as n-Methylpyrrolidone (NMP) used in the production of battery cells. “The NMP is the worst part of the slurry. It’s a nasty chemical that is definitely not good to breathe or get on your skin,” Greg Less, technical director at the University of Michigan Battery Lab, told me in 2023.

For Doherty, it feels as if managers are making things up as they go. “They’ll say we’re certified on something, and then the next day, say, ‘actually, no, that certification isn’t good.’ All sorts of problems can and have arisen from that.”