ICE Can't Erase What Lelo Juarez Built

Lelo with his wife and niece in the May Day march next to the sign that says “With No Fear.” Photo: David Bacon

In 2022 I went to Washington State for May Day, and the following year as well. Just south of Canada, in Bellingham and Mount Vernon, Community2Community and Familias Unidas por la Justicia celebrate the workers holiday in the tradition followed by the rest of the world. They march. For me, a child of the Cold War, when May Day was the forbidden Communist holiday, it's a time to appreciate how the world has changed. Brightly-painted hand-made signs and banners call out—“Another World is Possible!" —a May Day sentiment if there ever was one. Some demonstrations can be formal exercises. Theirs are filled with farmworkers and children chatting in Mixteco or Triqui, with students and earnest young men in religious collars, and of course with activists from a dozen unions.

Farmworkers clean a tulip field belonging to Washington Bulb. The workers are members of Familias Unidas por la Justicia. Benito Lopez is a leader of the union.

Both years I came a few days early. I wanted to see the tulip harvest, or at least the end of it, since it's almost over by May. Thousands of tourists come to see the flowers. Fields of solid red and yellow blooms stretch for miles, from Mount Vernon halfway to the ocean. Shiny BMWs and Acuras crawl bumper-to-bumper down tiny country roads, creating an urban-sized traffic jam.

Juana Sanchez is a worker in the crew cleaning a tulip field.

Both years I got up early, before the madness, and drove those same roads, as yet still empty. I wasn't looking for the flowers, though. Instead, I was keeping an eye out for beat-up Fords and Toyotas parked by the side of the fields, or dusty school busses transformed to transport labor. I was seeking the workers. I hoped I'd find the ones who stopped the harvest in the first year of the pandemic, using the power they'd discovered when they organized their independent union at the Sakuma blueberry farm a decade earlier. (See Trouble in the Tulips, and Why These Farmworkers Went on Strike.)

The tulip cleaning crew leaves the field.

Today one of those worker-organizers rots in a cell, in Tacoma's infamous Northwest Detention Center. Lelo (Alfredo Juarez, as his mother named him) was a teenager when Triqui and Mixtec indigenous workers rose up in the Sakuma fields and labor camps. As they fought for their union, Sakuma strikers put Lelo to work while he was still a boy. Because he'd gone to school in Washington he could translate easily back and forth from classroom English to the Spanish of the streets and the indigenous language of his family.

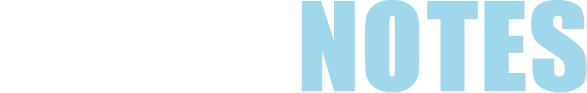

Lelo speaks to a May Day march of migrant farmworkers and their supporters, calling for unions and human rights.

It took four years to win a contract for berry pickers at Sakuma Farms. Indigenous Mexican migrants learned to use short walkouts to push up piece rates and protect each others' jobs. Some left the fields for days or weeks, traveling from campus to campus, from Seattle to San Diego, asking students to picket and boycott Driscoll berries, the giant company that bought the fruit they picked. In the end they won, and with that contract in hand, Familias Unidas por la Justicia became the voice for farmworkers across northwest Washington.

Two farmworkers on the machine.

As I drove through the early morning, I saw a small group of workers hoeing weeds among the giant leaves of overgrown cabbages. As usual, I stopped to talk, then take some photographs. It didn't take long before I asked them if they'd ever worked at Sakuma. The leader of the little crew proudly announced she and her workmates all belonged to Familias Unidas. That morning they were not laboring at a union job, but they had the union in their hearts.

Two farmworkers pick bulbs out of the dirt on the tulip machine.

Then I caught up with a larger crew cleaning the remaining flowers in a tulip field, and the experience was repeated. I'd just walked into the rows with my camera when someone called out my name. There was Benito Lopez, wearing his Familias Unidas sweatshirt, marking him as a member of the union committee. Benito stayed in my Bay Area house on one of those boycott journeys a few years before. He plays in a band and plays for FUJ and community fiestas, and his mirror sunglasses gave him away as a musician or a rocker as he worked down the row of flowers.

Benito Lopez cutting the tops of tulip flowers.

When the field was nothing but bare tulip stalks, and the petals from the last discarded blooms were trampled into the mud between the rows, the foreperson came to Benito to ask if the crew wanted to move to another field. It was late in the day by then, and perhaps they might want to go home. But the crew held an impromptu committee meeting in the dirt road, and decided they wanted to get a couple more hours in before quitting. There's no written contract with Washington Bulb in the tulips, but it was clear that the supervisor knew he had to get their agreement. That is the power that Lelo and Benito and the rest of the workers built.

Benito Lopez, Juana Sanchez and other members of Familias Unidas hold a meeting to decide if they will continue working in another field.

The next morning I saw a huge machine, motionless in the middle of what had been a tulip field the day before. I parked and walked down the dusty road from the highway, and found a crew eating breakfast. Some were men in blue coveralls, and the others were women in regular work clothes. They offered me their tacos. Eating has social meaning in a field, so we ate together and talked.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

The family of Benito Lopez at the Tierra y Libertad cooperative farm, started by the union.

The men were H-2A workers, who come from Mexico to do this work every year on temporary work visas. They clearly needed the work to support families back home. But I wondered if the regular tulip workers in the picking crews were ever trained to work on the huge rig. Those jobs probably pay better than cutting tulips and daffodils.

Maria Ramirez works in the tulip field.

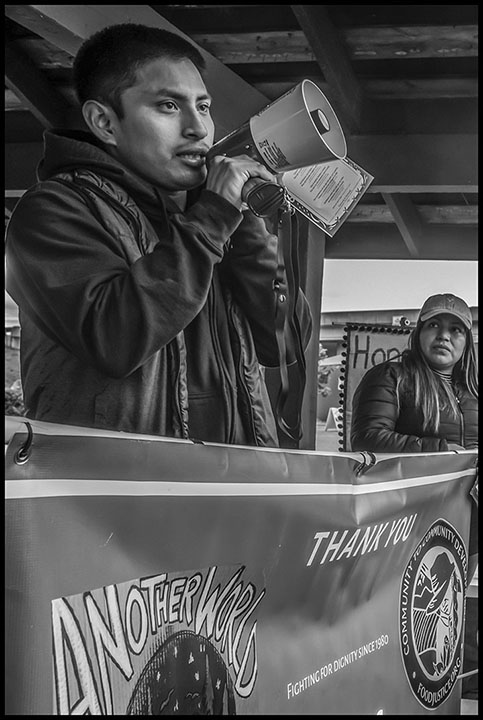

The workers in Familias Unidas por la Justicia have tried to find a way to fight for the interests of both groups—H-2A workers and local residents. During their organizing saga at Sakuma Farms, they had to defeat an effort to replace hundreds of strikers with H-2A workers. Their success in doing that ensured they could keep their jobs win the strike. Yet every year their marches carry banners honoring Honesto Silva, an H-2A worker who died from the conditions in a Washington field. When his co-workers stopped work after he died, Familias Unidas helped organize their protest before the company cancelled their visas and fired them. A worker is a worker, and everyone needs to be organized, the union says.

“Another World is Possible”

Breakfast over, the machine coughed to life and again began its ponderous travel down the now-bare field. As it clanked along it dug up the tulip bulbs, separated them from the dirt, and spat a stream of them into a gondola alongside. Behind it a small group of women gathered up any bulbs the machine missed. Tulip bulbs must be worth a lot, I thought.

Working behind the machine.

Now, looking at the images from those two years, I see the kind of hard labor Lelo gave the company as a worker in those flower fields. Then I thought of the work he gave the union, when he decided that the most important thing was to change the lives of the people who work in them. That was not an easy decision. His actions, and those of his workmates, have made some powerful people very angry. They are using his immigration status to remove him and throw him in a hole. By extension they threaten anyone else who dreams of doing what Lelo did. I can see the family Lelo has just started is out there on the May Day march, now facing such terrible danger.

As they cross the river into Mount Vernon during the tulip harvest, May Day marchers carry a banner remembering Honesto Silva, an H-2A worker who died in the fields. Another sign says “Without Workers There Are No Tulips.”

These photographs are just a few of the many I’ve taken since that first strike at Sakuma Farms in 2013. To me they show the hard reality of these workers’ lives, and their determination over years to change it. Getting Lelo out of detention will bring justice for him. And it will move that struggle a little further down the road.

David Bacon is a labor journalist and photographer, author of Illegal People: How Globalization Creates Migration and Criminalizes Immigrants and other books.

Donate to Alfredo "Lelo" Juarez's legal fund here.

A march protesting federal regulations making it more difficult to protect the rights of H-2A and resident farmworkers the H2-A guestworker program, on the anniversary of the death of Honesto Silva. The march stopped in front of the Ferndale Detention Center, where Lelo was later taken.

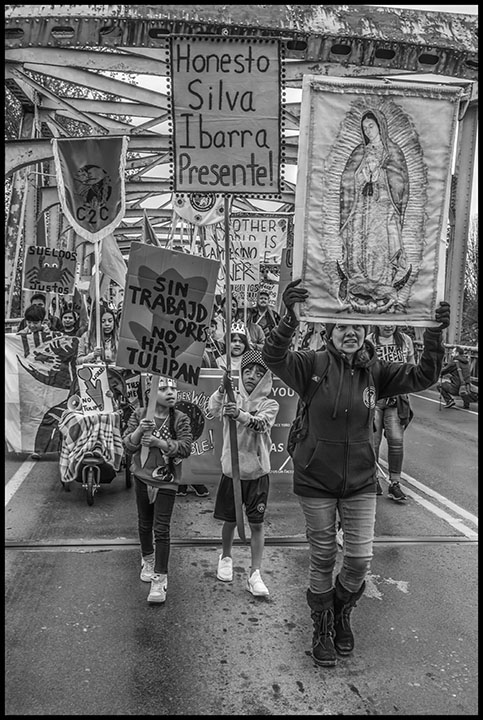

On the May Day march workers remind the growers that with no workers there will be no tulip harvest.

Foreman Jose Partida and other workers eat lunch in a tulip field belonging to Washington Bulb.

Maria Ramirez, Victoriana Galvan and Heidi Garcia collect bulbs missed by the big machine.